渴求过量的知识,是人类最原始的诱惑与罪恶

(1) In the entrance to the former of these—to clear the way and, as it were, to make silence, to have the true testimonies concerning the dignity of learning to be better heard, without the interruption of tacit objections—I think good to deliver it from the discredits and disgraces which it hath received, all from ignorance, but ignorance severally disguised; appearing sometimes in the zeal and jealousy of divines, sometimes in the severity and arrogancy of politics, and sometimes in the errors and imperfections of learned men themselves.

(1)作为开篇,为排除障碍,也可以说为了让我们静下心来对于学问尊严加以论证,以便能够更好地为人们所接受,不致暗中受到各种非议,我认为最好要从学问遭受的质疑与屈辱说起。这些质疑和屈辱主要源于无知,而这种无知通常带有伪装性:有时体现在神学家的狂热与嫉妒的情绪中,有时又体现在政治家的严苛与狂傲的态度上,还体现在学者自身的错误与缺陷里。

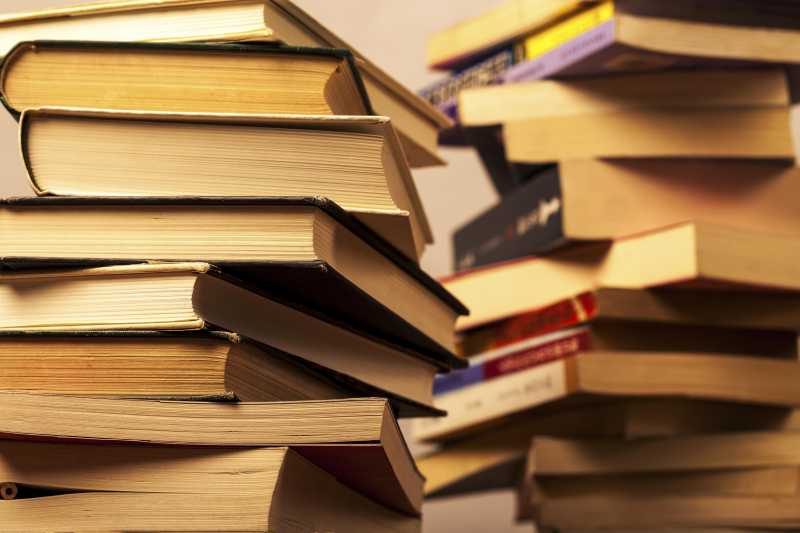

(2) I hear the former sort say that knowledge is of those things which are to be accepted of with great limitation and caution; that the aspiring to overmuch knowledge was the original temptation and sin whereupon ensued the fall of man; that knowledge hath in it somewhat of the serpent, and, therefore, where it entereth into a man it makes him swell; Scientia inflat; that Solomon gives a censure, “That there is no end of making books, and that much reading is weariness of the flesh;” and again in another place, “That in spacious knowledge there is much contristation, and that he that increaseth knowledge increaseth anxiety;” that Saint Paul gives a caveat, “That we be not spoiled through vain philosophy;” that experience demonstrates how learned men have been arch-heretics, how learned times have been inclined to atheism, and how the contemplation of second causes doth derogate from our dependence upon God, who is the first cause.

(2)据我了解,前人认为学习知识有诸多限制,须倍加小心;因为渴求过量的知识是人类最原始的诱惑与罪恶,并最终导致了人类的堕落;知识本身如同毒蛇,因此,一旦它进入人类思维,人便会自我膨胀,即“知识膨胀”。所罗门就曾警示道,“知识会让人自我膨胀。著书多,没有穷尽;读书多,身体疲倦。”在另一处他又提到,“因为多有智慧,就多有烦愁;知识越多,烦愁越多。”圣保罗也曾告诫道,“你们要谨防有人用他虚空的哲学扰乱内心。”经验显示,学者往往容易发展成极端的异教徒,学术昌明的时代也常倾向于无神论,而对第二动因的沉思又削弱了我们对于第一动因——上帝的信赖。

(3) To discover, then, the ignorance and error of this opinion, and the misunderstanding in the grounds thereof, it may well appear these men do not observe or consider that it was not the pure knowledge of Nature and universality, a knowledge by the light whereof man did give names unto other creatures in Paradise as they were brought before him according unto their proprieties, which gave the occasion to the fall; but it was the proud knowledge of good and evil, with an intent in man to give law unto himself, and to depend no more upon God's commandments, which was the form of the temptation. Neither is it any quantity of knowledge, how great soever, that can make the mind of man to swell; for nothing can fill, much less extend the soul of man, but God and the contemplation of God; and, therefore, Solomon, speaking of the two principal senses of inquisition, the eye and the ear, affirmeth that the eye is never satisfied with seeing, nor the ear with hearing; and if there be no fulness, then is the continent greater than the content: so of knowledge itself and the mind of man, whereto the senses are but reporters, he defineth likewise in these words, placed after that calendar or ephemerides which he maketh of the diversities of times and seasons for all actions and purposeqs, and concludeth thus: “God hath made all things beautiful, or decent, in the true return of their seasons. Also He hath placed the world in man's heart, yet cannot man find out the work which God worketh from the beginning to the end” —declaring not obscurely that God hath framed the mind of man as a mirror or glass, capable of the image of the universal world, and joyful to receive the impression thereof, as the eye joyeth to receive light; and not only delighted in beholding the variety of things and vicissitude of times, but raised also to find out and discern the ordinances and decrees which throughout all those changes are infallibly observed. And although he doth insinuate that the supreme or summary law of Nature (which he calleth “the work which God worketh from the beginning to the end”) is not possible to be found out by man, yet that doth not derogate from the capacity of the mind; but may be referred to the impediments, as of shortness of life, ill conjunction of labours, ill tradition of knowledge over from hand to hand, and many other inconveniences, whereunto the condition of man is subject. For that nothing parcel of the world is denied to man's inquiry and invention, he doth in another place rule over, when he saith, “The spirit of man is as the lamp of God, wherewith He searcheth the inwardness of all secrets.” If, then, such be the capacity and receipt of the mind of man, it is manifest that there is no danger at all in the proportion or quantity of knowledge, how large soever, lest it should make it swell or out-compass itself; no, but it is merely the quality of knowledge, which, be it in quantity more or less, if it be taken without the true corrective thereof, hath in it some nature of venom or malignity, and some effects of that venom, which is ventosity or swelling. This corrective spice, the mixture whereof maketh knowledge so sovereign, is charity, which the Apostle immediately addeth to the former clause; for so he saith, “Knowledge bloweth up, but charity buildeth up;” not unlike unto that which he deilvereth in another place: “If I spake,” saith he, “with the tongues of men and angels, and had not charity, it were but as a tinkling cymbal.” Not but that it is an excellent thing to speak with the tongues of men and angels, but because, if it be severed from charity, and not referred to the good of men and mankind, it hath rather a sounding and unworthy glory than a meriting and substantial virtue. And as for that censure of Solomon concerning the excess of writing and reading books, and the anxiety of spirit which redoundeth from knowledge, and that admonition of St. Paul, “That we be not seduced by vain philosophy,” let those places be rightly understood; and they do, indeed, excellently set forth the true bounds and limitations whereby human knowledge is confined and circumscribed, and yet without any such contracting or coarctation, but that it may comprehend all the universal nature of things; for these limitations are three: the first, “That we do not so place our felicity in knowledge, as we forget our mortality;” the second, “That we make application of our knowledge, to give ourselves repose and contentment, and not distaste or repining;” the third, “That we do not presume by the contemplation of Nature to attain to the mysteries of God.” For as touching the first of these, Solomon doth excellently expound himself in another place of the same book, where he saith: “I saw well that knowledge recedeth as far from ignorance as light doth from darkness; and that the wise man's eyes keep watch in his head, whereas this fool roundeth about in darkness: but withal I learned that the same mortality involveth them both.” And for the second, certain it is there is no vexation or anxiety of mind which resulteth from knowledge otherwise than merely by accident; for all knowledge and wonder (which is the seed of knowledge) is an impression of pleasure in itself; but when men fall to framing conclusions out of their knowledge, applying it to their particular, and ministering to themselves thereby weak fears or vast desires, there groweth that carefulness and trouble of mind which is spoken of; for then knowledge is no more Lumen siccum, whereof Heraclitus the profound said, Lumen siccum optima anima; but it becometh Lumen madidum, or maceratum, being steeped and infused in the humours of the affections. And as for the third point, it deserveth to be a little stood upon, and not to be lightly passed over; for if any man shall think by view and inquiry into these sensible and material things to attain that light, whereby he may reveal unto himself the nature or will of God, then, indeed, is he spoiled by vain philosophy; for the contemplation of God's creatures and works produceth (having regard to the works and creatures themselves) knowledge, but having regard to God no perfect knowledge, but wonder, which is broken knowledge. And, therefore, it was most aptly said by one of Plato's school, “That the sense of man carrieth a resemblance with the sun, which (as we see) openeth and revealeth all the terrestrial globe; but then, again, it obscureth and concealeth the stars and celestial globe: so doth the sense discover natural things, but it darkeneth and shutteth up divine.” And hence it is true that it hath proceeded, that divers great learned men have been heretical, whilst they have sought to fly up to the secrets of the Deity by this waxen wings of the senses. And as for the conceit that too much knowledge should incline a man to atheism, and that the ignorance of second causes should make a more devout dependence upon God, which is the first cause; first, it is good to ask the question which Job asked of his friends: “Will you lie for God, as one man will lie for another, to gratify him?” For certain it is that God worketh nothing in Nature but by second causes; and if they would have it otherwise believed, it is mere imposture, as it were in favour towards God, and nothing else but to offer to the Author of truth the unclean sacrifice of a lie. But further, it is an assured truth, and a conclusion of experience, that a little or superficial knowledge of philosophy may incline the mind of men to atheism, but a further proceeding therein doth bring the mind back again to religion. For in the entrance of philosophy, when the second causes, which are next unto the senses, do offer themselves to the mind of man, if it dwell and stay there it may induce some oblivion of the highest cause; but when a man passeth on further and seeth the dependence of causes and the works of Providence; then, according to the allegory of the poets, he will easily believe that the highest link of Nature's chain must needs he tied to the foot of Jupiter's chair. To conclude, therefore, let no man upon a weak conceit of sobriety or an ill-applied moderation think or maintain that a man can search too far, or be too well studied in the book of God's word, or in the book of God's works, divinity or philosophy; but rather let men endeavour an endless progress or proficience in both; only let men beware that they apply both to charity, and not to swelling; to use, and not to ostentation; and again, that they do not unwisely mingle or confound these learnings together.

(3)要找出这类观点的无知与错误之处,指出对它根本上的误解,我们便需意识到,那些人并未认真观察,细心思虑,人之所以会堕落,并不是因为关于自然与宇宙的纯粹知识,也不是因为一种能在伊甸园中根据其他生物的特性对其加以命名的知识,而是因为人类过于骄傲,自满于自身拥有的有关善恶的知识,并企图恣意妄为,不再遵从上帝的戒律,这也是一种诱惑。无论知识如何丰富,人类都不能自我膨胀。因为除了上帝和对上帝的冥思,一切都无法填充人类的心灵,更别提令其膨胀。因此,所罗门在提及眼、耳这两种人类探知世界的主要感官时曾明确指出,“眼看,看不饱;耳听,听不足”。只要容器大于内容,便永无充盈之时。知识本身与人类心灵亦复如此,而感官仅仅是向心灵汇报其所感知到的一切。所罗门在其编写的一部历书或称为编年史的后面也有类似表达,制定这部历书的目的在于区别不同时间和季节应从事的活动。他在书中总结说,“上帝造万物,各按其时显得美好。又将世界万物安置在世人心里。然而自始至终上帝的行为,人不能参透。”无疑这句话是在表明,上帝塑造了人类的心灵,使其如镜子或玻璃一般,感知宇宙万物的影像,并如眼睛乐于接收光亮一样欣然接受由此产生的印象。人类心灵不仅乐于接受万象万物,也喜于洞悉各类变迁所一贯遵循的规律与法则。尽管所罗门已暗示了至高无上总领一切的自然法则(他称为“上帝自始至终所做的工作”)不可能为人类所发现,但这并没有贬低人类的心智,只是说明其中存在着阻碍,如生命的短暂、精力分配不当、不良传统的传承及其他许多烦扰因素,而人类便是受制于这些条件。所罗门说:“人类的灵魂尤如上帝的明灯,上帝便是通过它来探索万物的奥秘。”于是,世上一切都不可能逃过人类的探寻与发掘,在某些方面人类甚至起着支配作用。如果人类心灵确实具有这些能力与容量,显然知识的范围与总数不论有多庞大,都不会产生任何危险,从而使其免于自我膨胀或超出自身能力范围;然而事实上,不论知识本身的数量多少,如不经任何纠正而全盘接受,那么这些知识之中便会混入一些毒素,造成不良影响,发酵、繁殖,以致过分浮夸或者膨胀。而可以纠正错误、解除毒素的调和剂便是仁爱,它可使知识显示出至高无上的一面。使徒在之前所引的话后又即刻附上:“知识令人傲慢自大,惟有爱心能造就人”。在另一处,又提到相似的内容:“我若能说万人的方言,并天使的话语,却没有爱,我就成了鸣的锣、响的钹一般”。这并不是说懂得人类话语和天使语言不是件好事,只是说如若言辞中缺乏仁爱,不利于大众公益、人类事业,那么,它就谈不上是具有实质价值的美德,只不过是空洞浮夸的吹嘘罢了。至于所罗门提到的对著述、阅读过度的谴责和知识带来的精神烦忧,以及圣保罗的警告,“我们不要被空虚的哲学所迷惑,”此类种种,人们需细细解读。诚然,它们很好地阐释了人类知识所受到的真正约束与限制,未经得任何压缩,但是却能够领会万物的普遍性质。因为知识所受的限制有三类:第一,“我们不能把幸福过多依赖于知识,而忽略人的死亡宿命;”第二,“我们运用知识获得宁静与满足,而不是厌烦与抱怨;”第三,“我们不可擅自观察自然以窥得上帝的秘密。”对于第一点,所罗门在书中另一处有极好的阐述:“我看得清楚,智慧远离无知,如同光明远离黑暗;聪明人睁大眼睛用心观察,愚蠢的人在黑暗中跌跌撞撞。但是我认为无论是智者还是愚者都有死亡大限。”至于第二点,知识偶尔会给心灵带来烦扰与忧虑,但仅是偶尔;因为所有知识和疑惑(这便是知识的萌芽)本身就能产生愉悦感,但当人类用自己的知识过度揣测,将其应用于自身个例,为自己服务,用来降低恐惧,满足欲望时,那么之前提及的心灵的烦扰与忧虑便会增加。到那时,知识不再是学识渊博的赫拉克利特所谓的“干燥的光,最佳的灵魂”,而是成为了情感浸透下的湿润之光。最后一点值得鞭辟近里地进行探讨,我们不能走马观花蜻蜓点水。如有人认为可以通过观察与探究感性的物质世界来获得这一束光,从而窥得上帝的本性或意愿,那么,他的确是被虚空的哲学扰乱了内心。知识产生于对上帝创造的万物与作品的沉思(对这些创造物本身而言),但上帝自身并不能产生完美的知识,有的只是各种疑惑,也可称作是零散的知识。柏拉图学派的一名学者对此有恰如其分的表述:“人的感知如同旭日,它向我们展示了大地万物,却又掩藏了天空与星辰。人的感知也是如此,它能发现自然万物,却弱化并隐藏了神的一切。”因此,他在后面提到,因而各领域高深学者均成了异教徒,企图凭借自己脆弱的感官之翼飞向神的领域,探求其奥秘。有人认为,过多知识使人自傲,令人趋向无神论,对第二动因的无知则使人更为虔诚地依赖上帝这一第一动因。针对这一观点,首先,我们不妨提及约伯问他朋友的话,“你会为讨好上帝而撒谎吗,就像人类为取悦他人而说谎那样?”上帝通过第二动因支配万物,这点是毫无异议的。若有人并不这么认为,那只是为取悦上帝,实则是一种欺骗,是对真理之主的不洁献祭。进一步来说,对哲学的一知半解可将人类引向无神论,但继续深究又可将其拉回宗教领域,这是不争的事实,也是经验之谈。因为在哲学入门之时,距离感官较近的第二动因即刻进入人们思想。若令其在此长时逗留,则可能致使人类遗忘至高动因;但如果继续前行,看到各动因之间的依存性,领会到上帝的伟大创造,那么,根据诗人的喻意,人们便很容易相信,自然链的最高连接点必须系在丘比特座椅的脚上。因此,总而言之,不要让人们对清醒抱以少许自负心态,也不要让人们误用了缓和的思想,还不能让人类认为自己可以记录上帝话语和作品,即神学和哲学的书籍中进行深入探索,彻底揣摩,相反,人们应当在两个方面都进行不懈努力,以取得不断进步。只有当人们意识到他们把这两方面都应用到获得仁慈宽厚而非自我膨胀中,以运用为目的,而非炫耀,而且,人们不可不明智地将这些学问错综糅杂,混为一谈。

大家都在看

-

揭秘人体之:最诡异的器官竞是它 在我们的人体中,隐藏着许多神秘而复杂的器官。其中,有一个器官常常被认为是最诡异的,它就是“阑尾”。虽然阑尾在许多生物学教科书中被描述为一个“无用”的器官,但近年来的研究却揭示了它可能具有更重要的功能。 ... 人类之最12-21

-

人体最好的状态就是阴在上,阳在下!可惜80%的人都颠倒过来了! 中医认为啊,人体最好的状态就是阴在上,阳在下!可以80%的人都颠倒了。大家好,我是樊医生。为什么说要保持“阴在上,阳在下”的状态才是最好的呢?我们人体的最上方就是头部了,头为诸阳之会,本身就是阳气最为充 ... 人类之最12-20

-

全球十大最著名的天文望远镜,中国天眼榜上有名 人们总是对外太空感到好奇。天文望远镜的诞生和发展促进了天文学的发展,扩大了我们对宇宙的认识。那你知道世界上有哪些著名的望远镜?下面世界之最网小编就给各位介绍下全球十大最著名的天文望远镜,中国天眼榜上有 ... 人类之最12-20

-

熔点最高的五大金属排名:钨排第一,熔点高达3422℃ 话说当今世界上有许多熔点高的金属,有的易碎、耐磨、抗腐蚀、坚硬且熔点高被广泛应用各个领域。它们有的也是许多国家的重要战略资源。那么,你知道熔点温度最高的金属有哪些呢?现在世界之最网小编为大家介绍熔点最 ... 人类之最12-20

-

人体最大的器官是什么你知道吗? “人体之最”系列小知识 你知道人体最大的器官是什么吗?让我们来猜一猜,是肺,还是大脑?还是心、肝、脾、肺、肾?不用猜了,都不是,我们来揭晓答案,人体最大的器官是——“皮肤” 皮肤指的是覆盖于人体全身表面 ... 人类之最12-18

-

中国历史上最强的五次地震,西藏察隅、墨脱1950年8.6级地震居榜首 我国位于亚欧板块、太平洋板块以及印度板块的交界处,因此在我国境内也存在着多条地震断裂带。在历史上,我国也曾记录到多次较为强烈的地震活动,其中等级超过8.0级的地震次数达22次,下面就和世界之最网小编一起看 ... 人类之最12-18

-

弗洛伊德的惊人观点:性欲不满竟是人类痛苦之源? 心理学家弗洛伊德的一句名言:“人类的一切痛苦,都是因为性欲得不到满足”,此语可谓“一石激起千层浪”,引发了广泛的争议和讨论。这一观点真的能“一言以蔽之”地解释人类所有的痛苦吗?让我们“抽丝剥茧”,深入 ... 人类之最12-16

-

人类历史上,最伟大的六位一流化学家,分别是哪六位? 人类历史上,最伟大的六位一流化学家,分别是哪六位?化学是一门在原子、分子水平上研究物质的组成、结构、性质、变化、制备和应用的自然科学,它是一门具有创造性和实用性的科学,化学家们通过不断的研究和发现,推 ... 人类之最12-16

-

心理学家弗洛伊德:“人类所有的苦楚,皆源于性欲的无法满足” 在现代社会中,心理健康无疑成为了我们共同关注的重要话题。越来越多的人意识到心理疾病不仅关乎个体的福祉,还与整个社会的和谐息息相关。生活的压力、传统观念的束缚,以及内心的挣扎,常常让人们感到窒息。在这个 ... 人类之最12-15

-

心理学家弗洛伊德:“人类的一切痛苦,都是因为性欲得不到满足” 想象一下,一个人站在十九世纪末维也纳的讲台上,面对一群穿着黑色礼服、戴着金丝眼镜的医学权威,说出“人的行为多半源于被压抑的性欲”这样的话。观众的脸色有多精彩?没错,这个引发医学界“地震”的人,就是西格 ... 人类之最12-15

相关文章

- 心理学家弗洛伊德:“人类的一切痛苦,都是因为性欲得不到满足”

- 人类历史上最接近神的男人——达芬奇

- 梅德韦杰夫的见证:人类史上最伟大的奇迹

- 一万多米深的马里亚纳海沟深处,人类最不希望看到的东西,出现了

- 人类最无私最纯真的诺言:把我的血抽一半给妹妹,每人活50年。

- 故宫博物院十大镇馆之宝,《清明上河图》排第一位

- 中国历史上发行量最大的五大古钱币,熙宁重宝排第一名

- 中国拍卖成交最贵古的五大钱币,咸丰元宝背“宝泉当五百"排第一位

- 于东来是人类有史以来最伟大的企业家,不接受反驳

- 全球十大 AI 产品使用人数排名:豆包排第二,ChatGPT排第一

- 中国十大金饰热爱地区排行:湖南垫底,浙江排第一名

- 黄仁勋荣获香港科技大学博士学位 称AI或是人类史上最重要技术

- 世界上最先进的十大科学技术,能源技术排第一位

- “夏娃理论”被质疑,中国的化石说明一切,人类的祖先到底是谁?

- 世界上最先进的十大战机,中国的歼-20榜上有名

- 人体7大营养素,你都吃对了吗?

- 世界上发电量最大的十大发电站,中国三峡水电站排第一位

- 对人类社会影响最大的十大发明,指南针和火药双双入榜

- 现代医药界最伟大的五大发明:青蒿素上榜,青霉素名列榜首

- 冷知识☞舌之奥秘:人类全身上下最强韧有力的肌肉

热门阅读

-

关于男人的15个世界之最,最长阴茎达56厘米 07-13

-

东方女性最标准的乳头(图片),看看自己达标吗 07-13

-

人体器官分布图介绍 五脏六腑的位置都在哪 07-13

-

木马刑是对出轨女性的惩罚 曾是满清十大酷刑之一 07-13

-

熙陵幸小周后图掩盖性暴力 至今保存于台湾博物馆 07-13

-

包头空难堪称国内最惨案件 五名遇难空姐照曝光 07-13

-

2022中国最新百家姓排名,你的姓氏排第几? 03-26

-

好玩的绅士手游有哪些?2022十大绅士游戏排行榜 10-18